Ramachandra Guha’s Gandhi

Gandhi's time in India ended differently than in Africa. Even before the bullets came for him, Gandhiji had begun to wonder if it wasn't time he left.

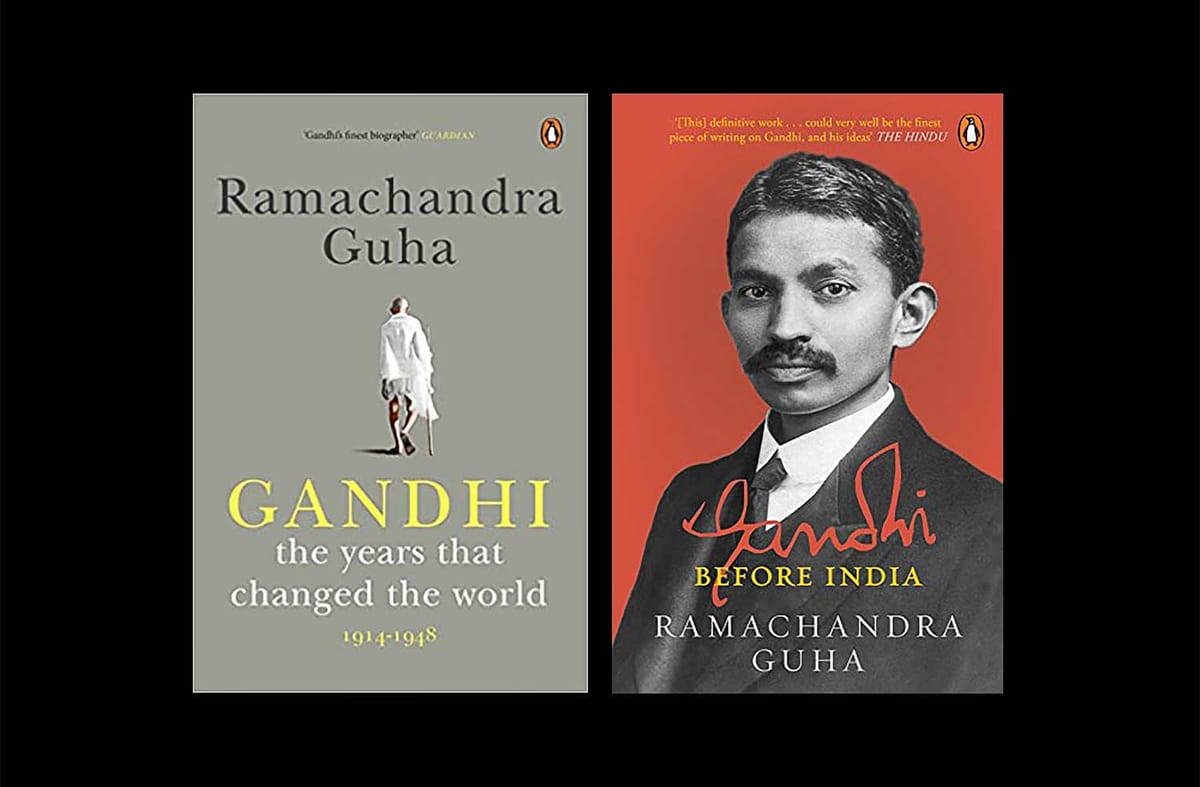

These last three weeks, I've been profitably engaged in reading Ramachandra Guha's brilliant second volume on Gandhi — from 1914 until his assassination in 1948. (Weeks prior, I read the first volume, Gandhi Before India.) Averaging 50 pages a day, experiencing Gandhi over three weeks, I absorbed the weight of his works over those thirty-four years.

When he moved back to India, arriving in Bombay in January 2015, Gandhiji was a satisfied man who had brought his Africa affairs to a decent closure, with arrangements in place for the continuance of what he'd begun there. He had been wanting to return for some time, seeing himself fit for the greater role there.

Once home, he took his time to get started, choosing to first study Indians, and India, through travelling across the colonial-country over a year. That done, when he began to organise his priorities, came the call from Champaran; the Rowlatt Act was passed; Jallianwala Bagh happened. Meanwhile, Gandhi had determined the eradication of untouchability, and Hindu-Muslim unity, as the first victories to be won before self-rule could be extracted from the British. How he confronted these challenges, the fresh ones and those festering for ages, established him in Indian minds. In five years he'd come to hold sway over the Indian masses — rich and poor, urban and rural, caste-Hindus and untouchables, Muslims and Sikhs and Parsis and Christians.

The first large-scale action was the non-cooperation movement, based on ahimsa and satyagraha. The campaign roused the subcontinent, with only a few dissenters, such as Muhammad Ali Jinnah and Srinivasa Shastri. Seeing the groundswell, and the possibilities, Gandhiji fancied Swaraj was around the corner — about a year away, it seemed. But soon he realised the march to freedom would be drawn out, with pitfalls at every turn, and roadblocks in and out.

Non-cooperation; the Salt March; Congress victory in provincial elections; the War and the refusal of Congress to back it without the promise of Swaraj; the Quit India Movement; the negotiations for self-rule and the second provincial elections; and Freedom and Partition and our own holocaust — these events marked the tortuous, torturous path to Independence.

Opposition All Round

Gandhi faced virulent and sustained opposition from many sources: Jinnah the constitutionalist, who didn't favour street protests, and who later defined the nation by religion; Ambedkar, who argued caste-Hindus could never take untouchability out of a faith whose very premise was caste; Mahasabhaites, who'd never reconcile to Gandhi's inclusion of the non-Hindu in Gandhian India; followers of valiant Bhagat Singh who couldn't imagine ahimsa taking India anywhere; and, in Congress itself, non-believers in Gandhi's methods, such as Bose. So, Indians weren't a single, united force pushing back the coloniser. They were disparate groups, some with base reasoning, some high-minded, all patriotic, but some bedding in turns with the British, agreeing with them, supporting them — even as other compatriots fought and suffered.

These differences frayed our already torn socio-political fabric, rendering the stitching hard in later, post-Independence years. Still, we have a democracy that's not altogether a failure; there's knowledge in our psyche of what is right and wrong for India; we are aware when we are at odds with what we should be doing — these are our hope that Indians will eventually rise up to where they belong. The learning comes in the main from the Mahatma, from what he spoke and wrote and fought for.

Speaking for Gandhi, his time in India ended differently than in South Africa. His last days were spent in anguish over the divisions; the unimaginable violence; Nehru and Patel drifting apart; the irreversible Partition. Even before the bullets came for him, Gandhiji had begun to wonder if it wasn't time he left.

Methods: Fasting And Writing

Gandhiji's fasts were successful, in that he got what he wanted in each case. But the fast was for when a course needed correction but faced stiff opposition — or when crisis cried out to be immediately dissolved. Most astute among men, he knew how much his key supporters needed to mobilise to meet his demands.

Mostly he used patient persuasion, through speech and the written word, communicating truthfully, without fear, without guile.

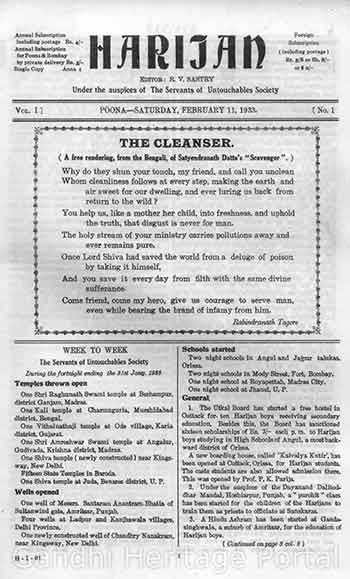

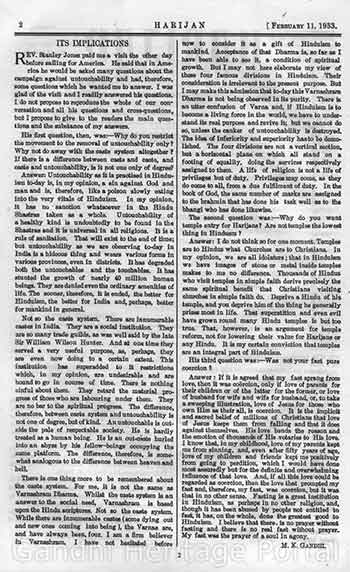

He used to great effect the print media: He published the journal Indian Opinion in South Africa. In India, he wrote in his periodicals Harijan and Young India until the very end. Through them, he reasoned with friend and foe, mobilised hartals and satyagrahas, articulated their purpose, and sustained his core arguments against untouchability, and for inter-faith unity.

Which makes me think, on a lighter note, that Gandhi would have loved blogging. Coupling reason with visible, transparent action, he'd blog with great success, commanding the highest following of all in the world. And yet Bapu would have spurned blogging because blogging stands on mass production and colossal consumption. So much change has happened since he passed — the economic wrongs and the environmental damage, for example — which he'd anticipated, presciently pointing out the ills our impulses would wreak on us. He'd sounded naïve then, comes across no different now, but viewed in the circumstances of our times, was his naïveté courage in thought and action on a level the rest of humanity so tragically lacks?