Locked Down Plantation, Elephants, Sandalwood Smugglers

It's a blue-topped bright-green world now during June, and more avians than ever in the twelve years I've known the place have flown into the plantation.

Locked Down Plantation

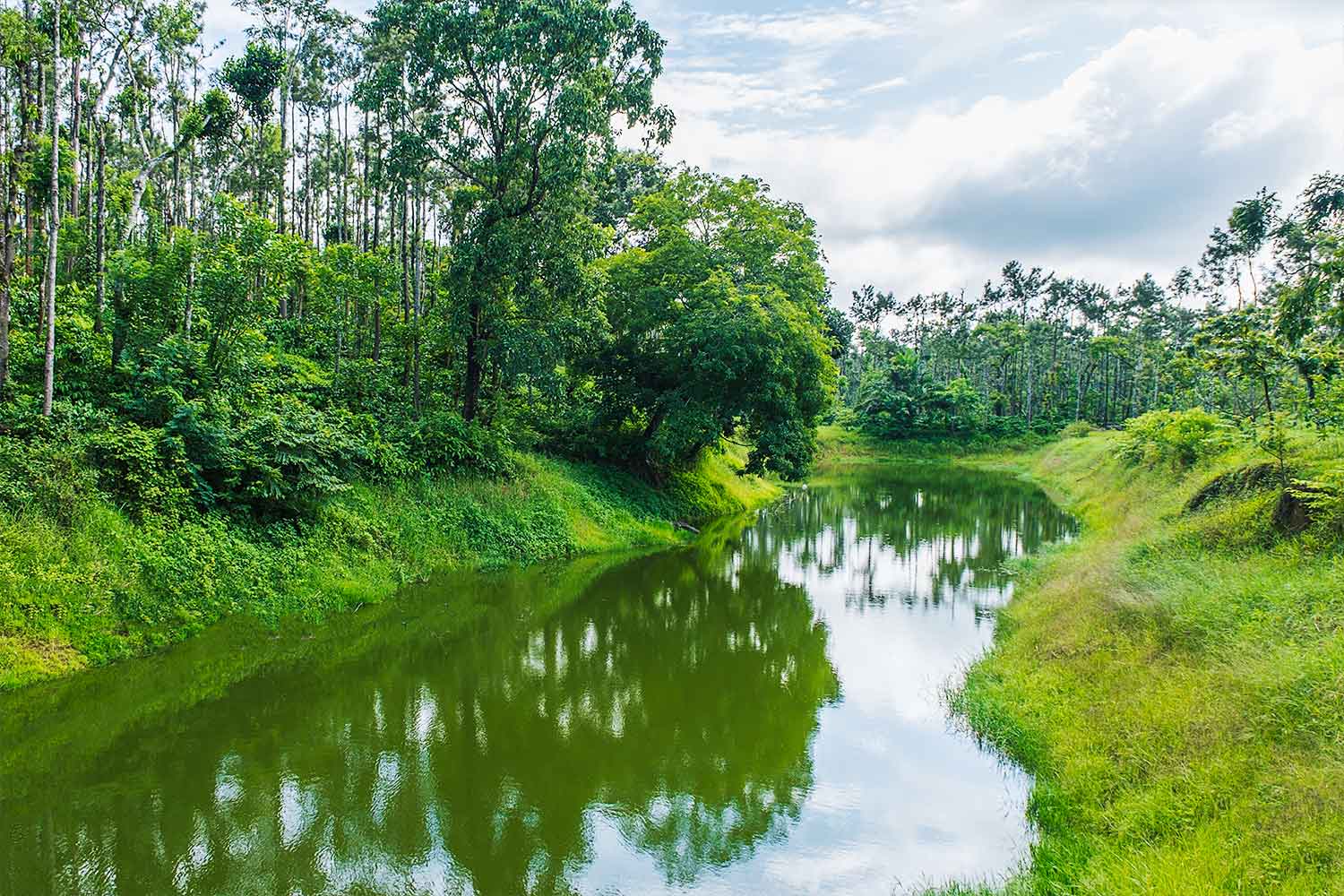

Back in our coffee plantation this weekend, after three months, I delighted in the lockdown-induced effusion of life there. It's a blue-topped bright-green world now during rainy June, and more avians than ever in the twelve years I've known the place have flown in — they're flashing colours and tweeting tunes not seen or heard in a long time. When I came down the bund of the main tank, a blast stopped me short, of the sudden flapping of four huge peafowls, which rose up and flew a pair each in opposite directions. They came down after a short flight and were instantly concealed. Their numbers have shot up, too.

The nights were glorious, with the coffee plants, the shade trees and the slopes and the hills around lit by the Strawberry Moon.

Elephant Country

About forty elephants have swarmed the wider area, and these days folks are okay with their presence. Still, while walking about, I heard dhadaki going off in the distance, and hurried away from the direction whence the sound came — of somebody chasing elephants out.

A lone elephant is roaming free on our plantation and roundabout. It is young, sports fresh-grown tusks and baby fat. I couldn't see it, but Dharmendra, our new plantation manager, sent me videos purportedly of the kid. It has been to our home, eaten off the jackfruit tree in the back, and although it is sweet-looking, a report from a week ago makes you wary of it.

On the neighbouring plantation, an elephant was sighted approaching a weeding gang. The workmen fled, and one of them fell. Responding to the commotion, the elephant started running as well, running with the folks than after them. It landed a foot on a leg of the fallen fellow.

"Most likely, this one did it. The only single hereabouts," says Dharmendra.

People are going about their business, though. The planters appeal to the forest officials, who tell them, "You must coexist."

Junga and His Gang

Sifting the registration records of our plantation the other day, I browsed the names of past owners. Over forty years ago, a Father Jeremiah, from Mangalore, owned the property. I've not known Jesuits as landowners. But it occurred to me that if Father Jeremiah had lived on the plantation while he owned it, he would've had some prize souls for harvesting — right along his northern boundary in the Malegalale and Honkaravalli villages.

In those times abundant sandalwood grew in these parts, whereas you hardly see them now. And, people say, olden-day sandalwood had girth, unlike the scrawny types of these days. Fragrant sandal, whether it grows on private property or in the commons, is government property. Cutting down and trading in that wood attracts a hefty fine, time in jail, and shame — excellent fertiliser that bred a gang of intrepid sandalwood smugglers.

Junga was the most daring among them. Some other names from the gang are Hassainar, Vittala, and Locksmith Chandru. They worked six days a week, cutting down nightly the sandal growing in the plantations, storing it in nearby concealments, and transporting it to Kerala. On the seventh day, the men washed, wore clean clothes, and walked about Honkaravalli, looking good, drawing attention, and revelling in it.

To transport the contraband to buyers, they'd lift cars in Bangalore, preferring the white Ambassador, newer the better. Locksmith Chandru went along to help open the door, his village knowing that if Chandru was going to Bangalore, a new car was coming. The car would be put to work immediately. They'd pack the sandal in front, in the back, in the boot, and take off, driving like in the movies, crashing through toll gates, careening on bare metalled roads, mud tracks, doing all the drama before the law. The best performer was Junga, who, all in a day, would zip to Kerala, deliver sandal, collect money, and rush back on the winding roads of the hilly jungly Western Ghats — in monsoon or in dry weather.

The men would've been good meat for Father Jeremiah to lend a soul to. These were armed thieves, ready to neutralise any impediment. The local police were in their pay. Cops coming from Mysore to nab them arrived scared, wanting to go back soon as they'd arrived. The gang went about its affairs with aplomb, partying before the thieving by the stream that runs along my (Father Jeremiah's) eastern boundary. The kids from the villages would go watch the drinking and (even join) the dancing. The adults kept an understandable distance, and Father Jeremiah must have done the same. Each of these men met a different, but an unhappy end. Some went to jail. One died crashing into a tree in Singapura village. Junga, tall and strapping, dashing like a movie star, was a survivor. He went on and on until he, too, made a mistake.

Hunting in Bangalore for their next transport vehicle, Junga spotted a spanking white Ambassador and brought it home. The trouble this time was, the thing belonged to a state minister.

A crack team found and gave chase to Junga, who drove his fastest ever, the police hot on his back. Reaching Malegalale, he hit the embankment of the culvert where the village begins. He survived the crash, but he must have stepped out with his gun. Because the police didn't take him in.

They shot him.